Italy's Supply-Side Troubles

Italy’s immediate crisis is a demand-side crisis. The financial crisis in late 2008 and insufficiently stimulative monetary policy on the part of the European Central Bank since then have led to lower output and bigger budget deficits.

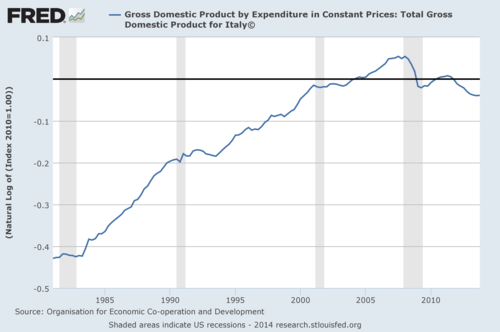

But Italy has longer run problems as well. The graph above shows the natural logarithm of real GDP in Italy relative to its value in mid-2004. When people talk about “bending the curve” of medical costs, they are talking about the kind of falling growth rate that this graph shows for Italy’s GDP, long before the Great Recession.

I am always on the lookout for articles that give a bit more vivid picture of what can go wrong on the supply side of an economy. “Can Italy Find Its Way? Resistance to Change Means Slow Recovery” by Marcus Walker and Deborah Ball in the April 29, 2014 Wall Street Journal is an excellent example of just such an article. All quotations below are from Marcus and Deborah.

Taxes

Sometimes people think of the supply side as primarily a matter of taxes. In Italy, there are high taxes, but they are high partly because other taxes are not paid:

Taxes on labor are particularly high. One reason is that taxes that would normally help spread the burden—including on the incomes of small businesses and the self-employed—are widely dodged.

Italian entrepreneurs evade over 50% of the income taxes they owe, while people living off investment income skip over 80%, the country’s central bank estimates. The heavy taxes on payrolls deter companies from hiring and weaken consumers’ spending power, economists say.

Slow Permits

A big factor in Italy’s supply-side malaise is the difficulty of establish any new shop. This issue is sprinkled throughout Marcus’s and Deborah’s article:

1. Bernardo Caprotti was a 45-year-old entrepreneur when he agreed to buy a suburban plot of land for a new supermarket.

Building permits recently came through. He’s now 88.

2. Red tape is one factor that deters businesses from growing. …

In 2012 British Gas PLC threw in the towel on a €500 million gas import terminal in southern Italy after struggling for over a decade to get the necessary permits.

It is a problem familiar to Mr. Caprotti. “If we start something today, it could take 15 years to finish,” he says. “Then you’re lost because you find that the size or the location doesn’t work anymore.”

Impaired Property Rights Because of Slow Courts

Property rights are crucial for economic efficiency, but property rights are created by law. A slow legal system impairs property rights:

Italy’s court system also spooks businesses: Routine contract disputes take more than three years on average to resolve in court—and much longer if there are appeals. Italy’s lawyers, who outnumber their French brethren fourfold, have resisted efforts to streamline a judicial system that offers rich opportunities for lengthy proceedings. At the end of 2012, there was a backlog of 9.7 million cases, according to the International Monetary Fund.

General Resistance to Change

Marcus and Deborah make the case that tolerance change is necessary for economic growth:

In societies whose populations aren’t growing, sustainable growth comes from improving productivity, or the efficiency of the economy’s supply side. And that requires constant change: Europe’s Achilles’ heel.

But the status quo is powerful in Europe, and in Italy particularly:

Entrenched interests and hardened habits have accumulated in Europe over decades, slowing once-dynamic economies to a crawl, and are now proving difficult to overcome. From bureaucrats to businesses, unions to pensioners, interest groups vigorously defend the status quo, even when it leaves no one satisfied. …

The roots of the problem, say many Italians, lie in how vested interests in the private and public sectors gum up the economy, preventing change that replaces old practices with new, more efficient ones, and repeatedly frustrating political attempts to shake up the country.

It adds up to “deep-seated cultural obstacles to growth,” says Tito Boeri, a professor at Milan’s Bocconi University who is one of Italy’s top economists. “In Italy you define your identity in terms of your membership of some specific interest group,” he says, making it hard to rally support for any notion of the common good.

Regulated professions such as lawyers and pharmacists consistently beat back efforts to break their cartels. Powerful bureaucrats bog down the implementation of new laws for years. And Rome’s political class is so quarrelsome that governments last little more than a year on average.

It used to matter less. Italy’s economy grew rapidly in the postwar era despite a stonewalling bureaucracy, legions of tiny companies and a fragmented, often corrupt political system. But growing was easier then: Relatively poor Southern European countries mainly had to copy technology from more-developed economies such as the U.S., and use it to churn out goods cheaply.

Making the wheels turn in an advanced economy requires the efficient rule of law, reliable public administration and more capital and expertise than many mom-and-pop businesses can muster, says Fabiano Schivardi, an economist at Rome’s Luiss University who has studied the stagnation of swaths of Italy’s business sector.

“Our institutions were good enough for an economy that was catching up, but they’re not good enough any more,” he says.

Family Businesses Resistant to Change

Not all resistance to change in Italy is at the collective decision-making level. Individual families running businesses also are often resistant to change at a level far beyond what is seen in the US:

Many family business owners prefer to stay small, sticking to the staff and customers they already know and trust, says Matteo Bugamelli, senior analyst at the Bank of Italy. “Often, all of the family wealth is in the firm, and there isn’t the risk appetite that you need to invest and grow,” he says. …

“The culture here is be the padrone in your own house,” he says, using the Italian for “boss.” Many family entrepreneurs “don’t trust outsiders and prefer to bring in their own son, even if he’s not well qualified,” he says.

Institutional Resistance to Change

Organized groups resist change in many ways.

Italian unions have also often dug in their heels to resist change. For years, union battles held up efforts to save the national airline, Alitalia, which struggled to get its labor costs down. Last fall, as the carrier faced imminent bankruptcy, unions agreed to pay cuts and more-flexible working terms.

Fear often lies behind unions’ defense of the status quo. Redundant blue-collar workers might never find jobs again in Italy’s sclerotic jobs market.

Some foreign entrepreneurs are discovering just how tough it remains to penetrate the Italian market.

Uber, the app-based car service that launched in Italy last year, says traditional taxi drivers have verbally abused its drivers, who respond to customers’ orders sent by smartphone. The taxi union denies any aggression, and says its members have paid a fortune for their taxi licenses, which now trade at about €170,000, and offer a public service that needs to be protected.

“During a period of change, there are some whose jobs are under threat and a sense of protectionism sets in,” says Benedetta Arese Lucini, general manager of Uber in Italy. “Unfortunately, Italy is afraid of changing.”

Low Government Capability

Finally, in Italy, the national government often seems powerless in relation to the ability of local vested interests to resist change:

Even when leaders pass reforms into law, change doesn’t necessarily follow. Bureaucrats who must implement laws by issuing administrative decrees often stall, dilute them or render them incomprehensible, say reform-minded officials. When the government of Enrico Letta fell in February, about 500 laws had been passed but not implemented. Among them: a measure to reduce the number of permits required for companies to do business and a law to digitize certain processes to simplify dealing with the government.

“There is a great deal of difficulty in moving the bureaucracy and the whole machinery of the state,” said Graziano Delrio, undersecretary to the prime minister, in an interview. “There has been this approach of making modest changes, but we need to make a leap in how it all works.”

Former Premier Mario Monti tried to inject more free-market competition in service sectors where regulation protects incumbents’ profits. Striking taxi and truck drivers, railway workers, pharmacists, lawyers and gas-station owners protested his overhaul attempts and lobbied parliament to water them down. Even the weakened measures that passed into law have often made little difference, because the public administration hasn’t acted on them, Mr. Monti says.

Final Thoughts

It is not that easy to think of good solutions for Italy’s supply-side problems. I think I would start with

- Reforming the courts. This is a precondition for item 2.

- Firmly establishing the legal supremacy of the national government over local governments, especially when the national government is giving more freedom to entrepreneurs.