Avoiding Fiscal Armageddon

I believe the continued existence of our species is of great value. Therefore it is worth paying a great price to reduce the chances of a nuclear Armageddon by even a little bit. There is reason to believe that if Iran gets nuclear weapons, it will significantly raise the chances of further nuclear proliferation–which in turn will raise the chances of nuclear war further down the road. Thus, to my mind, preventing Iran from getting nuclear weapons trumps any other foreign policy or economic goal right now. Though we should fervently hope that through diplomacy the price is lower, we should be willing to pay whatever price is required, even if that price includes literal battle deaths as well as the figurative body blow of higher oil prices to an already ailing world economy.

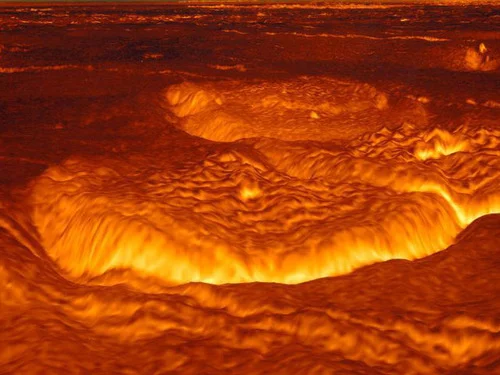

The surface of what was once called “our sister planet” Venus is not a pleasant place for human beings. Scientists believe that Venus became so hot because of a runaway greenhouse effect. We don´t know how likely it is that the Earth will go down this road, but the possibility is terrifying. All of the other possible harms from increasing the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide–such as floods, hurricanes, famines, extinctions of many plant and animal species–pale in insignificance compared to even small increases in the chances of a runaway greenhouse effect that would truly transform Earth into Venus´s sister planet. To my mind, the scientific and popular discussion about global warming should focus more on what we know about the possibility of a climate change Armageddon in the form of going down the Venus road and how we can know more, thanon the lesser horsemen of floods, hurricanes, famines, extinctions of plants and animals, and so on.

This graph of government spending as a percentage of GDP (from Jim Bianco) isn´t as scary as the other two pictures, but it only includes Federal spending, and absent decisive action, the worst is yet to come. The reason the worst is yet to come is simple: the U.S. population is getting older as birth rates drop and the Baby Boomers (from an earlier era of high birth rates) reach retirement age. Other than defending our country and acting as the world´s policeman, the big expenses of the Federal government are the programs intended to take care of older Americans: Social Security, Medicare, and the part of Medicaid that goes to pay for nursing-home costs of people who have used up their own resources. Everything else the Federal government does pales in comparison to Defense and taking care of older Americans (although Obamacare could add a large enough government responsibility for the medical care of younger Americans to compete in this contest). Thus, more older Americans means more expenses of the Federal Government.

As I have only begun to explain in my posts “What is a Supply-Side Liberal?”“Can Taxes Raise GDP?” and my current favorite post “Why Taxes are Bad,” the taxes needed to support high levels of government spending come at serious cost. This is likely to continue to be true even if we try to be very clever (as we should try to be) at raising revenue with the least possible distortion. (On one way to raise some revenue while actually reducing distortion, see “A Supply-Side Liberal Joins the Pigou Club” and “Henry George and the Carbon Tax.”) So at the end of the day, after all our efforts to raise revenues in ways that are not too harmful to the many important objectives we put under the label “the economy,” there will be a limit to how large a fraction of GDP should be devoted to government spending.

For the sake of argument, let´s suppose we decide that–except in temporary emergencies–that Federal, State and Local governments combined should spend no more than half of GDP. How can we set up constitutional limits to achieve such a goal? It won´t be easy. As I wrote in “Leading States in the Fiscal Two-Step”:

… fiscal discipline is hard for governments—so hard that most governments are not capable of fiscal discipline without balanced budget requirements that are so inflexible they cannot easily handle economic emergencies.Given the unpredictability of real-world events, it is not possible to fully define what constitutes an economic emergency in advance as flexibly as would be desirable, but in the absence of hard and fast, but inflexible rules, governments have a temptation to chronically declare economic emergencies.

It´s hard, and maybe impossible. But let´s try. A balanced budget amendment won´t do it, since it would still be possible to tax and spend a large fraction of the (possibly smaller) GDP pie. A limit on taxes won´t do it, since the Federal Government is good at deficit spending. What we need is a rule that goes directly toward the goal: a direct limit on the fraction of GDP that is allowed to go to government spending.

There are complications. In particular, we need to (1) be able to get the rule passed, (2) make it hard to wiggle around the rule once it is in place, (3) be able to deal with emergencies and (4) avoid tempting the government to skimp on investing for the future.

(1) Getting the spending ceiling passed. The Republicans have been successful at making a big deal of the periodic need to raise the ceiling on the national debt. Suppose that the next time the debt ceiling needs to be raised, they said “We are willing to make increases in the debt ceiling automatic. All we want in return is immediate legislation and passage by Congress of a matching constitutional amendment that limits government spending by all levels of government to less than half of GDP." I think that the Democrats would lose politically by opposing this; if they opposed it, they would be admitting that in the future they planned to take more than half of GDP for government purposes.

(2) Making the spending ceiling stick. My idea here is simple. If government spending at all levels (Federal, State and Local) is more than 49% of GDP (according to a modified formula discussed below), the President of the United States has full power to cut Federal spending of any type in any way that he or she chooses down to the level that makes total government spending 49% of GDP. If government spending at all levels is more than 50% of GDP, the President of the United States is required to cut Federal spending to bring total government spending down to less than 50% of GDP–and of course is allowed to go further down to 49% if he or she chooses. Since the members of Congress value their own power, they would be unlikely to actually pass a spending bill that went above the 49% level, since that gives away a lot of their power to the President. So the likely outcome is that budget negotiations would proceed much as they do now, but Congress would never propose anything that pushed total government spending above 49% of GDP according to the formula. The one exception is if they thought they didn´t have the self-discipline to do what needed to be done and wanted the President to take the political burden from them. One reason to leave the President full flexibility on how to cut is that he or she would only be in that situation if Congress had given up on trying to control spending even though not trying to control spending themselves meant giving away a big chunk of their power to the President.

3. Designing a formula that allows for emergencies. Designing a rule that can deal with recessions, wars and other emergencies is complicated, but I think can be done. The first step is to use five-year averages for a number of quantities that tend to go up and down with the business cycle. I am going to give a list of things I would use five-year averages for. These are going to be things that can move around even if Congress hasn´t done anything in terms of regular budget legislation. The list: GDP, government spending on unemployment insurance and welfare, spending by state and local governments, interest payments on the debt (which are counted as spending), and military spending. The five-year average for military spending would include only a cobbling-together of the most recent 60 months that were not during a period of declared war. The five-year average for unemployment insurance and welfare and state and local spending would include only a cobbling-together of the most recent 60 months that were not during a period when the 3-month Treasury bill rate was below a .25% annual rate, which is meant to leave out periods of such great economic emergency that the Fed has already gone to its limit on reducing short-term government interest rates. The five-year average for GDP would be the greater of (a) the average over the last five years and (b) a cobbling-together of the most recent 60 months when the 3-month T-bill rate was above .25%.

There are several points to make about this formula. In a recession (according to a standard story) having unemployment insurance payments and welfare payments go up somewhat helps to stabilize the economy. These increases in spending are given some leeway by not being counted fully right away. Also, I am hoping that previously putting in place a Federal Medicaid Contribution Prepayment and Escrowing program–as proposed in my post "Leading States in the Fiscal Two-Step”–would make state government spending go up in recessions. This too would be given extra leeway by not being counted fully right away. And unemployment insurance spending, welfare spending, and state and local spending during periods when the Fed had already brought interest rates down to near zero would be fully exempted from the calculation. Similarly, a military spending spike in a given year would only be partially counted in that year, and not counted at all in the formula if during a period of declared war. And the spending limit would be in relation to GDP as it was before a serious recession. Finally, using the five-year average for interest payments on the Federal debt cushions the effect of any change in interest rates on how tight the spending ceiling is.

Looking at the other side of the ledger–the possibility of having the purpose of the rule subverted–there are several points to make:

- It is not that easy to wiggle around the rule in the long run using the 5-year average since spending more in one year then tightens the effective limits in each of the following 4 years.

- A period of economic emergency is effectively determined by the Fed (by having interest rates very low), not Congress or the President, so that does not present too much temptation.

- I think formal declarations of war are taken very seriously.

There is one other feature that may not be obvious but is also important in providing discipline. I am proposing to have the GDP numbers and the spending numbers be nominal amounts, which means that there is no inflation adjustment that Congress could tinker with. Doing the five-year moving averages for all of GDP but for only some types of spending means that the spending ceiling would effectively be tighter if inflation is higher. So this spending ceiling actually provides some discipline against Congress pushing the Fed toward too much inflation. (I don´t think the Fed acting on its own would try to cause extra inflation just to tighten the spending ceiling.)

One last issue with the formula is that one might worry that State and Local government spending will trend up so much that the Federal government can´t do its job. The answer to that is simple: if that becomes a big problem, the Federal Government has the power under its authority to regulate interstate commerce to limit State and Local spending to some reasonable maximum.

4. Capital Budgeting. Having roads and bridges in key places is important for economic growth. I don´t see a big problem with allowing the Federal Government to do the same kind of thing as local governments do with millages. If a ten-year bond is issued to pay for a road that lasts longer than that, it is OK to count just the annual payments on that ten-year bond as government spending for the purposes of the spending ceiling. The reason to go to the trouble to set up capital budgeting rules is to avoid giving Congress an incentive to neglect important investments. But note that the spending ceiling still bites. In each of ten years the money being paid for the road would mean the Federal Government is required to spend less on other things. To avoid chicanery, I would make ten years the longest payment period allowed for capital budgeting, even for things that might last longer.

Something that doesn´t require explicit capital budgeting, but is somewhat similar, is the way that Federal Lines of Credit (as proposed in my post “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy”) would interact with the spending. The key is to make clear in the rule that Federal loans (which Federal Lines of Credit provide to individuals in order to stimulate the economy) are only counted as spending when repayment of those loans is behind schedule. Any loan that was being paid off on schedule would not be counted as government spending. And a loan that fell behind in a previous year but got back on schedule this year would be netted out against other loans that fell behind.

Though I know the word “bailout” has a bad odor these days, if bailing out banks ever again became necessary to stabilize the financial system, bail-out loans could be treated similarly: only counting loans in actual arrears on payments as having been government spending. The risk that loans might not pay off in the future would not be counted as government spending. Even if the loans are ultimately going to go bad, the key here is to spread out when the government´s losses are counted as government spending, so that the government can do the bailouts if absolutely necessary. There should be a big debate about bailouts, but I don´t want to tie the governments hands in a true emergency, so the spending ceiling I am proposing does not attempt to stop bailouts.

Without decisive action, I fear that we will end up with government spending more than half of GDP. I think it will be much easier to get a spending ceiling like this enacted while it still seems shocking to think of running more than half of our economy in one way or another through the government. Avoiding fiscal Armageddon will not be easy in any case, but it will be easier if we set up good rules now to limit a possible torrent of spending in the future.