Why I Am a Capitalist Roader

There are many things that are messed up in our economy and in our society. These things often get blamed on “Capitalism.” But it is the fundamental principles of Capitalism that are keeping things from being worse—much worse—than they are. Let me give you my version of the fundamental principles of fostering prosperity, among which the principles of Capitalism are an important part.

Making Benefitting Society the Only Way to Get Rich. The most fundamental principle for fostering prosperity is to develop institutions that make benefitting society the only way to get rich:

Property rights are an obvious part of this: if you are allowed to steal, then you have an obvious path to trying to get rich that doesn’t benefit society.

The same goes for prohibitions on extortion: if you can get paid by saying “I’ll torch your store if you don’t pay me protection money,” there is again an obvious path to trying to get rich that doesn’t benefit society. (Muggings are a simpler version of the same thing.)

Prohibiting lying is also important. Lying can be a way of getting rich at someone else’s expense instead of getting rich by benefitting society.

Note also that it is hard to have secrecy without being driven or tempted to lie to protect that secrecy. To the extent secrecy is allowed, it should be closely regulated in order to avoid bad consequences from deceptive secrecy that exceed benefits of secrecy. My own personal opinion is that our society is a bit too pro-secrecy. We act as if people have an inherent right to keep secrets without asking them to make the case that the right to keep secrets in a particular context is going to make the world a better place. A right to keep secrets in some contexts makes the world a better place. A right to keep secrets in other contexts makes the world worse—sometimes much worse.

In a complex economy such as ours, there are many other highly technical things we need to get right to make benefitting society the only way to get rich. As a society, we have been neglectful of this design problem in the last 50 years. An important chunk of criticisms of “Capitalism” are criticisms of this neglect. I give some examples in “Odious Wealth: The Outrage is Not So Much Over Inequality but All the Dubious Ways the Rich Got Richer.”

(Note that an indirect way to benefit society to enhance the rewards for people who directly benefit society. For example, family members play an important role here; many people have worked a lot harder because they had a family to support.)

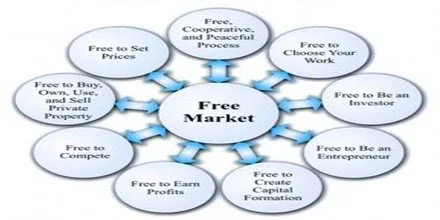

The Free-Market Principle. The next principle for fostering prosperity is the free-market principle of staying close to allowing any two people who want to make a trade (often of money for work, a good or a service) to make a trade. The reasoning behind this is that if both people want to make the trade, it suggests they think that trade will make each of them better off. Why not let them both become better off?

Any departure from this free-market principle should bear a heavy burden of proof that it does enough good to warrant the harm of preventing pairs of people who want to trade from both becoming better off. The need for tax revenue to provide public goods combined with concerns about poverty can provide an adequate justification for some departure from this free-market principle (I discuss those concerns in my inaugural post “What is a Supply-Side Liberal?”) In practice, many departures from the free-market principle that people advocate and many that get enacted are quite ham-handed. (For example, I think there are better approaches than the minimum wage. See “Inequality Is About the Poor, Not About the Rich” and “Oren Cass on the Value of Work.”)

Interestingly, anti-trust and anti-monopoly policies are part of this free-market principle. The government often discourages mutually beneficial trades by policies such as anti-construction policies that keep house prices high and occupational licensing rules that ‘Keep the Riffraff Out!’ Private companies also often discourage mutually beneficial trades by making it costly for people to switch to buying from a competitor. This should be (and to some extent is) discouraged by law. A good example is that tech companies acting to make interoperability and portability difficult violates the free-market principle. Another example is noncompete agreements that try to prevent an employee from going to a competitor. (It is often claimed this is necessary to protect trade secrets. But noncompete agreements have been proliferating far beyond what is needed to protect trade secrets. And letting companies protect trade secrets has to be justified, as I mentioned above. Letting companies protect trade secrets is in the same category as letting companies get patents, copyrights and trademarks, which all raise non-trivial policy questions.)

Even immigration restrictions are a way of blocking mutually beneficial trades; excessive immigration restrictions badly violate the free-market principle. For example, one has to put a very low weight on the benefits immigrants get from coming to the United States to oppose a big increase in legal immigration that includes appropriate provisions for encouraging assimilation. (Note that this is about economic participation of immigrants. Rules for political assimilation of immigrants are a different question. On that question, experience suggests it is unwise to have a group permanently have second-class political status as is true for immigrants in many countries. I think, however, it is possible to have up to an 18-year delay in getting voting rights without having the harms that come from a group permanently having a second-class political status.)

The Magic of the Price System. In practice, even a quite imperfect application of the free-market principle leads to a price system emerging. Any trade of money for work, a good or a service has an obvious price. If there is any freedom in choosing the price at which trades happen, those prices will carry a lot of useful information. (This is true even when prices are legally set but people make blackmarket transactions ignoring those laws. The legally fixed price doesn’t carry much useful information, but the blackmarket price does.)

Justin Lahart’s October 15, 2021 Wall Street Journal article “At Times Like These, Inflation Isn’t All Bad” confuses relative price changes—some prices going up more than others—with inflation, which is all prices and wages going up in lockstep. But change “inflation” to “the price system giving smart signals to the economy through relative price changes” and his article becomes a wonderful paean to the price system. Relative price changes tell the economy which way we want it to adjust. Let me quote a few examples from his article, with different passages separated by added bullets:

The pandemic has brought about changes in what we want to spend our money on and where we want to live and work that could prove persistent. Appliance prices aren’t up just because of supply snarls, for example, but because the Covid crisis increased the appeal of suburban living. So even if supply chains get fixed, demand could still be hard to meet, with prices continuing to rise as a result.

… the pandemic brought on was a massive increase in demand for goods, versus services. At first, this seemed entirely temporary: People were buying more stuff like videogame consoles and groceries because they were hunkered down at home. But even though the vaccine rollout and the easing of Covid restrictions has increased demand for services such as restaurant meals, demand for goods has shown staying power.

… That change in preferences is helping drive a divergence in inflation as well. Wednesday’s inflation report showed prices for consumer goods were up 9.1% from a year earlier, while services prices were up 3.2%. [That is, on average the prices of goods went up 5.9% relative to the prices of services.]

If more people keep working from home some of the time, for example, they will spend less money at lunch joints near their offices, and more on groceries.

Similarly, if businesses continue to hold many client meetings virtually, they will spend less on travel, and more on tech equipment. Personal-computer makers are betting that a higher number of workers will need more than one computer as a result of remote-work arrangements, translating into higher PC demand post-pandemic.

More people moving to the suburbs or smaller cities, and people who live in the suburbs working from home more often, could equate to more demand that suburban and smaller-city businesses need to meet. There does appear to be a divergence in what is happening with prices depending on population size: Overall consumer prices in areas with over 2.5 million people were up 4.8% from a year earlier in September, while prices in areas with 2.5 million or fewer people were up 5.9%. [That is, on average prices in suburbs and smaller cities have gone up 1.1% relative to prices in large cities.]

Demand-driven price increases carry an important message to businesses that are benefiting from them: You can make even more money if you can supply more. That entails buying new equipment, opening new locations and, most important, hiring additional workers. Meanwhile, businesses that experience weaker demand often can’t lower prices, in part because cutting worker wages isn’t feasible.

… [relative price changes] can help facilitate the economy’s response to shifts like the current one because it encourages expansion where demand is rising. It also helps draw workers away from moribund businesses where wages aren’t rising because inflation is cutting into how much those workers’ paychecks can buy.

Capitalism: The Price System Operating Over Time and Across Projects. Capitalism proper is an extension of the price system across time. “Capital” means the things needed in advance for production and sales that will only be completed later. “Capital” can also mean the funds used to buy those things needed in advance for production and sales that will only be completed later. Occasionally, an entrepreneur will be able to provide those funds themself. But entrepreneurial talent and already having a pile of ready funds do not always go together. So typically an entrepreneur looks for investors to help fund a project. Some investors simply loan money (which might not get paid back if the borrowing company or individual goes bankrupt). Others buy stock so that they have an equity stake that is worth more the better the project does and worth less the worse the project does.

The great thing about capitalism is that investors will work hard to figure out which are the best projects to invest in. Projects that are likely to succeed financially and therefore provide investors the best return are more likely to be of substantial value to society than projects that are likely to fail financially.

So far, I have talked about new projects. Capitalism is also crucial for directing funds to things that should be scaled up and denying funds to things that should be allowed to gradually scale down.

Finally, a form of Capitalism I call “Vulture Capitalism” is extremely useful in helping to wind down outmoded activities that should be wound down more quickly. As I say in “Odious Wealth: The Outrage is Not So Much Over Inequality but All the Dubious Ways the Rich Got Richer,” being a vulture capitalist and firing a lot of people is so painful to most emotionally normal people that you might not want hang out with someone who finds this an attractive career, but vulture capitalists serve a very important social function of sending workers looking for jobs that are more valuable for society than the outmoded job they were in.

Vulture capitalism is something we do relatively effectively in the United States. Many other countries impede this winding down of outmoded activities by government regulation and their economies suffer for it. One of the key examples of this was the transformation of retail led by Walmart. The US economy grew a lot because of that transformation of retail. Other countries didn’t see the same growth and productivity improvements because they had policies that tried to prevent existing retailers from going under.

Getting Interest Rates Right. In addition to getting the right projects funded, a Capitalist economy needs to make sure that the total volume of funds demanded for projects equals to total volume of funds supplied at the relatively full level of employment called the “natural rate of employment.” The relevant set of prices are interest rates, including the extra “premia” that are added to safe short-term rate to compensate for risk and for funds being committed for a long term. (The interest rate implicit in stocks is sometimes called “the required return.” It includes a risk premium and a premium for a stock representing a long-term investment.)

In theory, getting interest rates right takes care of itself in the long run, but in the short run, getting the overall level of the whole panoply of interest rates right is the job of the central bank: the Fed in the US, the European Central Bank in the euro-zone, the Bank of England in the UK, the Bank of Japan in Japan, etc. Thus, as things have evolved and improved, central banks have become a crucial part of the workings of a Capitalist economy.

Even Partial Capitalism is Valuable. Nothing here is directly about politics. China is not a democracy. But China benefits from deploying many of these principles for fostering prosperity. It usually protects property rights. It allows people to get rich by benefitting Chinese society. It allows a lot of economic exchanges to take place quite freely. It benefits from the magic of the price system. Even though China does a lot of politically directing funds run through state-owned banks to state-owned firms, it does allows private firms to raise funds. So China doesn’t allow as much scope for Capitalism, but it gets a lot of mileage from the Capitalism that it does allow. China does have a central bank, the People’s Bank of China, but it also tries to get the total amount of funds demanded to equal the total amount of funds supplied at relatively full employment by ordering more or fewer loans by state-owned banks. Capitalism is so powerful that a little bit can go a long way. And the US benefits from having even more Capitalism. Although China’s population is enough bigger than that of the US that the total size of its economy might exceed the total size of the US economy sometime in the next few decades. (See the graphs in “Benjamin Franklin's Strategy to Make the US a Superpower Worked Once, Why Not Try It Again?) However, China is unlikely to match US GDP per person any time in my lifetime or yours.