Evaluating the Idea that Estrogen Replacement Therapy Causes Breast Cancer against the Bradford Hill Criteria

One false thing in the world is that the conventional wisdom says estrogen replacement therapy and the closely related hormone replacement therapy cause breast cancer on the basis of quite dicey evidence. It matters for women’s lives, especially because estrogen replacement therapy and hormone replacement therapy (which also has estrogen as a key ingredient) have many health benefits, as well as quality-of-life benefits. I have two previous posts on this:

Hormone Replacement Therapy is Much Better and Much Safer Than You Think

Standard Hormone Replacement Therapy Doesn't Cause Breast Cancer

These previous posts explain why the experimental evidence doesn’t say what the conventional wisdom seems to think it does.

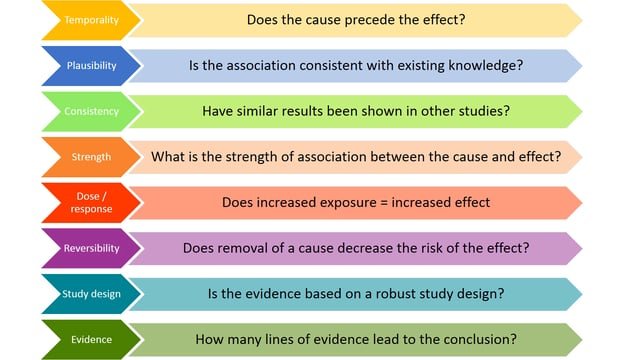

As for non-experimental evidence, the Bradford Hill criteria are often used in medicine and other areas as a way to think about evidence for causality. The excellent book Estrogen Matters by Avrum Bluming and Carol Tavris (shown at the bottom of this post) contrasts how strong the Bradford Hill criteria look for the idea that smoking causes lung cancer and how weak they are for the idea that estrogen causes breast cancer. You can see a list of the 8 Bradford Hill criteria at the top of this post; Avrum Bluming and Carol Tavris use a somewhat different version of the Bradford Hill criteria, which also adds the ruling out of alternative explanations as a 9th criterion (about which they don’t have much to say). I’ll intersperse indented quotes from Estrogen Matters with my own commentary after each of the other eight points:

… Using Hill’s framework, is the link between estrogen and breast cancer supported?

Strength: The link is unsupported. Most of the correlations published by the WHI and other investigators were neither strong nor statistically significant by conventional standards.

Let me say here that there is also a lot of p-hacking going on to try to get to bare statistical significance or close.

Consistency: The link is unsupported. Most published reports find no consistently increased risk of breast cancer associated with ERT. On the contrary, the results could not be more inconsistent: Between 1975 and 2000, forty-five published studies examined the relationship between breast cancer and ERT. Of these, 82 percent found no increased risk; 13 percent found a very small increased risk; and 5 percent found a decreased risk. In that same twenty-five-year period, of twenty published studies of HRT, 80 percent found no increased risk, 10 percent found an increased risk, and 10 percent found a decreased risk.

This point speaks for itself.

Specificity: …

The link is unsupported. The overwhelming majority of breast cancer patients have never taken estrogen, and the vast majority of women who have taken hormones have never developed breast cancer.

The link isn’t specific, but specificity is mainly a test of causality when there is one main cause of something. When something is one cause among many, we should still worry about it even though it is not a “specific cause” in the Bradford Hill sense. So unlike the lack of statistical significance (“strength”) and consistency, I don’t see the lack of specificity as totally damning. However, many women may make decisions about estrogen replacement therapy based on the idea that the link with breast cancer is much stronger than indicated by “The overwhelming majority of breast cancer patients have never taken estrogen, and the vast majority of women who have taken hormones have never developed breast cancer.”

Temporal relationship: The link is unsupported. Taking estrogen does not always, or even frequently, precede the onset of the disease. The risk of breast cancer increases with age—even after menopause, when estrogen declines, and even among women who never took estrogen.

Here we have a natural experiment: estrogen goes down after menopause. The drop is often steep enough to make a regression-discontinuity analysis reasonable. Breast cancer risk shows no quick drop at menopause.

Dose-response relationship: The link is unsupported. Study after study finds no consistent increased risk of breast cancer in women who have taken ERT or HRT for five years, ten years, or fifteen years. If cumulative exposure to estrogen is a risk factor in breast cancer, why did the Nurses’ Health Study and the Million Women Study find that risk only among current users rather than past users? Some investigators assert that early menarche and late menopause, which would provide a woman with more exposure to estrogen in her lifetime, are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. But they are not. Four separate studies have examined the breast cancer risks to women who started their periods between the ages of twelve and seventeen as compared to the risks for women whose periods started at age eleven or younger. In two of these studies, no differences in risk were found. In the other two, a significant reduction in risk was found only among women who started their periods at age seventeen and older; but they, like those whose menarche began before age eleven, represent a very small outlying percentage of the population. None of the comparisons for any of the other ages resulted in differences that were significant in any of the four studies.

Lifetime exposure to estrogen doesn’t seem to matter, which is strange, given that cancers often develop slowly.

Plausibility: The link is unsupported. Surely, the most disconfirming evidence for the claim that estrogen causes breast cancer is this: the administration of estrogen has been shown to have beneficial effects even in women with advanced breast cancer. For example, in 1944 Sir Alexander Haddow, director of the Institute for Cancer Research at the University of London, reported that 25 percent of his patients with advanced breast cancer improved when given high-dose estrogen,64 and other researchers subsequently have gotten the same or better results. Oncologist Bruno Massidda and his team at the University of Cagliari, Italy, reported remission in 50 percent of advanced breast cancer patients treated with estrogens, and so did Reshma Mahtani and colleagues at the Boca Raton Comprehensive Cancer Center. Gabriel N. Hortobagyi and colleagues at the MD Anderson Cancer Center reported that the most effective therapy for metastatic carcinoma of the breast was combined estrogen-progestin. James Ingle and colleagues at the Mayo Clinic demonstrated better survival among breast cancer patients treated with diethylstilbestrol (DES), a form of estrogen, compared to tamoxifen, as did Per Eystein Lønning and colleagues at Haukeland University Hospital in Norway. And the pioneer cancer researcher V. Craig Jordan and his research team demonstrated that both high and low doses of estrogen can shrink cancerous breast tumors.

Estrogen is actually a treatment for breast cancer!

Coherence: The link is unsupported. Using the mosaic method of knowledge, the more pieces we add, the clearer the overall image should become. That is what happened in confirming the relationship between smoking and lung cancer, and it is precisely what has not happened in the persistent efforts to confirm a relationship between estrogen and breast cancer.

The evidence just isn’t coming together. One can go too far by saying only one type of evidence (however equivocal) is worth paying attention to. Eventually, one should be able to make sense of the great bulk of the evidence—more complex evidence as well as cleaner evidence.

Experiment: The link is unsupported. In 1999, breast cancer rates began to decline. The WHI investigators claimed credit, maintaining that thanks to their 2002 warning that HRT was a cause of breast cancer, the number of women taking hormones plummeted—and thus did not develop breast cancer. However, their claim had several fundamental flaws. First, the decline began three years before the WHI published anything. Second, in Sweden and Norway, women stopped taking HRT at about the same rate that American women did but had no additional drop in rates of breast cancer. And third, because breast cancer usually takes years to become clinically detectable, how could a drop in the rate of breast cancer be related to stopping HRT one year prior? The WHI authors responded by saying that’s because when women went off estrogen, they removed a stimulus to the growth of already present but not yet detectable (subclinical) breast cancer. If that were so, however, the decreased incidence should have been confined to small, early, noninvasive breast cancers; it was not. It occurred almost entirely with invasive breast cancers.

Let me contrast this with a result that really did show something for another cancer. After the discovery that Helicobacter pylori caused stomach ulcers, the incidence of stomach cancer around the world went way down. That was a good piece of evidence that Helicobacter pylori can cause stomach cancer: the new treatment for stomach ulcers by antibiotics to kill Helicobacter pylori had the right timing to have reduced stomach cancer if Helicobacter pylori sometimes causes stomach cancer.

If estrogen causes breast cancer at all, it isn’t at all in the way that most people imagine. The way most people imagine has been clearly disproven.

For organized links to other posts on diet and health, see: