Christian Kimball: Doubting Thomas

I am pleased to have another guest post on religion from my brother Chris. You can see other guest posts by Chris listed at the bottom of this post.

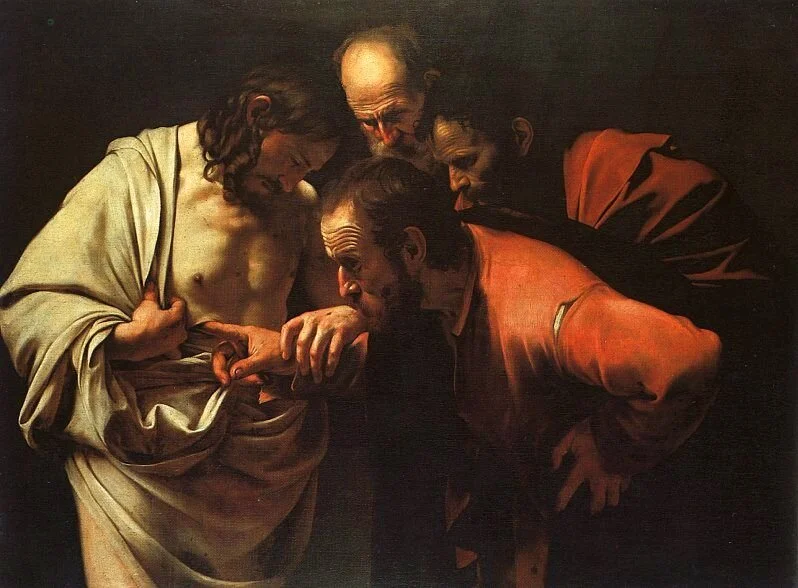

Doubting Thomas

The Octave Day of Easter or Sunday after Easter is variously called White Sunday, Renewal Sunday, Low Sunday (Anglican; 20th century Roman Catholic), Divine Mercy Sunday (21st century Roman Catholic), Antipascha (Orthodox), or Thomas Sunday (especially among Byzantine Rite Christians). By any name, the traditional gospel reading for this day is the story of Doubting Thomas.

In John 20 (but not the other Gospels) we read about Thomas who said

Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and thrust my hand into his side, I will not believe. (John 20:25 KJV)

The phrase “doubting Thomas” has come to be a negative term. Just check out Wikipedia: “A doubting Thomas is a skeptic who refuses to believe without direct personal experience.” It’s the “refuses” that signals moral judgment. They will say "if only you would choose to believe, all would be well. Just choose."

I am a self-confessed doubting Thomas. As I have written elsewhere:

I am a skeptic, an empiricist, a Bayesian. . . . A skeptic questions the possibility of certainty or knowledge about anything (even knowledge about knowing). An empiricist recognizes experience derived from the senses. A Bayesian views knowledge as constantly updating degrees of belief. In a functional sense, in the way it works in my life, I only know anything as a product of neurochemicals and hormones in the present.

Isn’t it possible that Thomas’ “I will not believe” is a simple statement of fact? As opposed to the childish playground taunt “prove it!”, maybe he was just saying “Guys, it won’t happen. Sorry about that but it’s how I’m built.”

What is important to me is that Jesus came. What modern criticism of doubters and skeptics would hint at is an alternate ending where Jesus went away, shunning Thomas the unbeliever. But what we’re taught is that Jesus came. Jesus came and said, “Peace be unto you. Reach hither thy finger, and behold my hands; and reach hither thy hand, and thrust it into my side.” And Thomas replied “My Lord and my God.”

Yes, maybe there is a message that skepticism is second best, second to believing without seeing. If that is so, I’ll accept second place. Because I have no choice, because I cannot do otherwise. For me, the important message is that Jesus came to Thomas. And Thomas saw and knew.

My “testimony” to fellow unbelievers is to be a doubting Thomas if that is how you are built. Jesus Himself proved it's OK. And maybe somewhere, someday, maybe on the road, maybe not in the middle of a church, Jesus will come to you. Too.

Chris circulated this essay among a small group of people before its appearance here. So it comes with an instant comment section:

>I think this is a perennial topic. I like the idea that there are people naturally constituted as skeptics who still need to be ministered to.

>I don't think Thomas was chastised for his skepticism. After all, it is difficult to believe that a dead person is no longer dead. I think he was chastised because he refused to believe the testimonies of many honorable men that he knew. To clearly understand what they are testifying of, to be able to question them thoroughly, and yet to doubt what they are saying, is to put yourself in the prideful position of being a superior potential witness: "I would not have been so easily fooled had I been there."

>I read D&C 46:11-14 as instructive:

For all have not every gift given unto them; for there are many gifts, and to every man is given a gift by the Spirit of God. To some is given one, and to some is given another, that all may be profited thereby. To some it is given by the Holy Ghost to know that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and that he was crucified for the sins of the world. To others it is given to believe on their words, that they also might have eternal life if they continue faithful.

To my way of thinking, if it was not Thomas’ gift to believe on their words, then he is not “accountable” for rejecting the testimony of witnesses and desiring to see for himself.

>But for the skeptic, "believing on their words" is hard.

>Agreed but I wouldn't use "But." All have not every gift is to say some--i.e., skeptics--do not have the "gift" to believe on their words. Quoting scripture is a way to say it is not a fault or failing (for an audience that gives credence to scripture), but simply part of the human condition.

>The testimony that the Holy Ghost can deliver to people is not the same kind of truth that a court of law seeks to establish. The testimony that Thomas' fellow apostles offered to him was the former type.

>The various kinds of testimony—of the Holy Ghost, of a trusted friend, of an otherwise anonymous neighbor—does make sense to me. People do make distinctions and weight them differently and take multiple factors into account in assessing the strength and reliability. I place more weight on the words of a trusted friend. That’s almost tautological—that’s what “trusted” means to me. Many religious people argue that the testimony of the Holy Ghost is of a different class, a different kind of testimony or knowledge. Like a direct line to knowledge or the ultimate source. It doesn’t work that way for me. Certainly, some evidence and some testimony is better or more persuasive than others, but I remain a skeptic throughout. Others have told me they are like me, so I don’t feel alone or an isolated instance of a skeptic. Although I cannot know, in my imagination Thomas was like me.

>If someone claims that the Holy Ghost told them something, that is for their benefit only, unless the message is from a church leader. Then I will follow it because that's my duty as a member, not that I necessarily believe it. I still need evidence that appeals to my sense of reason.

>Is it the words of the church leader you have a duty to follow? Or is it the testimony of the Holy Ghost to you about those words that you have a duty to follow?

>Prophets, priests, and ministers, have a tendency to communicate that (a) they know, and (b) listeners have an obligation to believe on their words. A skeptic says it doesn't work that way for me, as a statement of fact. In effect, this discussion is about the conflict between the attempt to impose an obligation and the observed fact that it doesn't happen.

>I remember reading the account in the New Testament for the first time myself and thinking Thomas's response to the others' statement as most reasonable. I had heard negative comments about Thomas and his supposed unbelief as though it were denial. The sort of short-hand comments people throw around when describing others. But when I read the account for myself, it read naturally, that Thomas didn't doubt the others' belief in their belief or their reality of their experience. I'm glad Thomas was not there that first day Christ returned. That gives me hope there will come a time when I too will know.

>Is knowing better than having faith? Maybe “knowing” will never be my gift and maybe “having faith” is the greater gift, or the gift for me.

Don’t miss these other guest posts by Chris:

Christian Kimball: Anger [1], Marriage [2], and the Mormon Church [3]

Christian Kimball on the Fallibility of Mormon Leaders and on Gay Marriage

In addition, Chris is my coauthor for

Don't miss these posts on Mormonism:

The Message of Mormonism for Atheists Who Want to Stay Atheists

How Conservative Mormon America Avoided the Fate of Conservative White America

The Mormon Church Decides to Treat Gay Marriage as Rebellion on a Par with Polygamy

David Holland on the Mormon Church During the February 3, 2008–January 2, 2018 Monson Administration

Also see the links in "Hal Boyd: The Ignorance of Mocking Mormonism."

Don’t miss these Unitarian-Universalist sermons by Miles:

By self-identification, I left Mormonism for Unitarian Universalism in 2000, at the age of 40. I have had the good fortune to be a lay preacher in Unitarian Universalism. I have posted many of my Unitarian-Universalist sermons on this blog.