The Federalist Papers #9 A: There Has Been Technological Progress in Practical Principles of Republican Government—Alexander Hamilton

In his introduction to the 9th number of the Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton boldly claims that there has been technological progress in the principles of Republican government. He first reminds readers of how bad things used to be even for cities and nations that had periods of considerable freedom and democracy. Then he very explicitly claims that there has been progress:

The science of politics, however, like most other sciences, has received great improvement. The efficacy of various principles is now well understood, which were either not known at all, or imperfectly known to the ancients.

Finally he lists key principles of republican government that had been discovered. Leaving for a future post his next theme of how larger republic may be more stable, here is his list, with my added bullets:

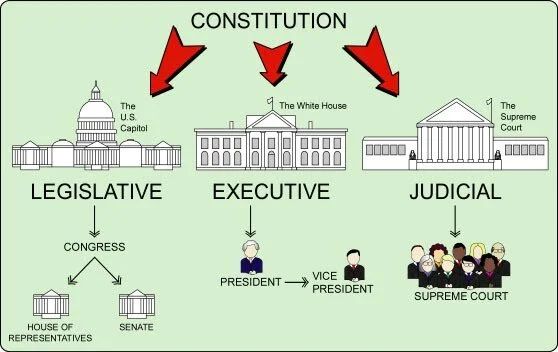

The regular distribution of power into distinct departments;

the introduction of legislative balances and checks;

the institution of courts composed of judges holding their offices during good behavior;

the representation of the people in the legislature by deputies of their own election:

He then again, in this specific context, asserts that there has been progress in understanding of the principles of stable republican government:

… these are wholly new discoveries, or have made their principal progress towards perfection in modern times. They are means, and powerful means, by which the excellences of republican government may be retained and its imperfections lessened or avoided.

Below is all of this in context:

|| Federalist No. 9 ||

The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection

For the Independent Journal.

Author: Alexander Hamilton

To the People of the State of New York:

A FIRM Union will be of the utmost moment to the peace and liberty of the States, as a barrier against domestic faction and insurrection. It is impossible to read the history of the petty republics of Greece and Italy without feeling sensations of horror and disgust at the distractions with which they were continually agitated, and at the rapid succession of revolutions by which they were kept in a state of perpetual vibration between the extremes of tyranny and anarchy. If they exhibit occasional calms, these only serve as short-lived contrast to the furious storms that are to succeed. If now and then intervals of felicity open to view, we behold them with a mixture of regret, arising from the reflection that the pleasing scenes before us are soon to be overwhelmed by the tempestuous waves of sedition and party rage. If momentary rays of glory break forth from the gloom, while they dazzle us with a transient and fleeting brilliancy, they at the same time admonish us to lament that the vices of government should pervert the direction and tarnish the lustre of those bright talents and exalted endowments for which the favored soils that produced them have been so justly celebrated.

From the disorders that disfigure the annals of those republics the advocates of despotism have drawn arguments, not only against the forms of republican government, but against the very principles of civil liberty. They have decried all free government as inconsistent with the order of society, and have indulged themselves in malicious exultation over its friends and partisans. Happily for mankind, stupendous fabrics reared on the basis of liberty, which have flourished for ages, have, in a few glorious instances, refuted their gloomy sophisms. And, I trust, America will be the broad and solid foundation of other edifices, not less magnificent, which will be equally permanent monuments of their errors.

But it is not to be denied that the portraits they have sketched of republican government were too just copies of the originals from which they were taken. If it had been found impracticable to have devised models of a more perfect structure, the enlightened friends to liberty would have been obliged to abandon the cause of that species of government as indefensible. The science of politics, however, like most other sciences, has received great improvement. The efficacy of various principles is now well understood, which were either not known at all, or imperfectly known to the ancients. The regular distribution of power into distinct departments; the introduction of legislative balances and checks; the institution of courts composed of judges holding their offices during good behavior; the representation of the people in the legislature by deputies of their own election: these are wholly new discoveries, or have made their principal progress towards perfection in modern times. They are means, and powerful means, by which the excellences of republican government may be retained and its imperfections lessened or avoided.

Here are links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War