A Nonsupernaturalist Perspective on Meridians in Chinese Medicine

Link to the Wikipedia article “Meridian (Chinese Medicine)”

Certain aspects of traditional Chinese medicine have impressive empirical support. This is not surprising; there are surely some areas in which trial and error for thousands of years should be able to home in on effective procedures. (Personally, I have had acupuncture treatments. It was actually in the first year I started my blog. I was so excited by my blog that I wasn’t sleeping. I went to the acupuncturist to get help in calming down a bit. It seemed to help.)

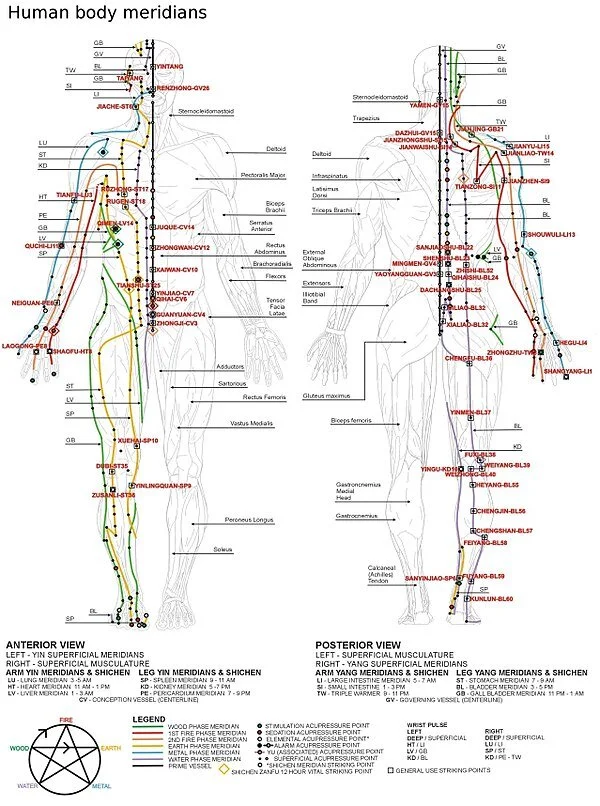

Although important chunks of Chinese medicine pass empirical muster as effective procedures, what doesn’t pass muster is the theory of Chinese medicine: the explanation Chinese medicine gives for why Chinese medicine works. The theory of Chinese medicine involves a substance called qi—which has no counterpart in Western physics. And it involves meridians in specific places along specific paths in the body that have no counterpart in Western anatomy to the surface claims of Chinese medicine.

In “What Do You Mean by 'Supernatural'?” I use inconsistency with modern physics as my definition of “supernatural.” By that standard, Chinese medicine relies on the supernatural in explaining its own workings. Note that the inconsistency with modern physics is no small thing. If a physicist were able to detect qi and, say, incorporate it into refashioned quantum field theory, that would be truly remarkable.

But I think there is a way to rescue the meridian system, with all its specificity, while staying fully consistent with modern physics. It is well known that there are parts of the brain that are specialized for attending to sensations and initiating actions for particular parts of the body. What if the meridians are not in the body in the locations the charts say, but rather in the brain’s “map” of those parts of the body? That is, meridians might represent relatively strong neural pathways between areas of the brain that specially attend to the various points on the meridian. This might or might not be true and would need to be investigated, but it is not particularly unlikely. On this view, qi, too, is easy to understand: it is simply neural signals among different parts of the brain (which are in turn associated with different parts of the body). Neural signals are remarkable, but as far as we know, there is nothing supernatural about them.

The bottom line is:

Don’t dismiss the part of Chinese medicine based on meridians too quickly.

Don’t think that the usefulness of the part of Chinese medicine based on meridians is any reason to believe in the supernatural.

I suspect that this perspective will not seem very satisfying to most practitioners or recipients of Chinese medicine. But this perspective is, in fact, fully consistent with many of the activities of Chinese medicine.

Update, October 11, 2020, 10:22 PM: It looks like the evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture is flimsier than I thought. See the Wikipedia article on acupuncture. It has been called a “theatrical placebo.” Of course, among placebos, theatrical ones can be especially powerful. But in particular, the evidence that using the meridians to place the needles aids effectiveness is weak. So what remains of the point of this blogpost? That even if the meridians are meaningful guides for placing acupuncture needles, it doesn’t mean there is any supernatural qi.

Related Posts: