The Federalist Papers #2 A: John Jay on the Idea of America

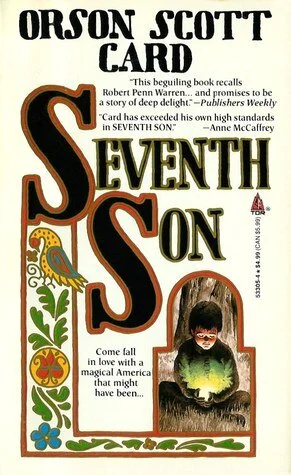

In his fantasy alternate history of America and the origins of Mormonism, Seventh Son, Orson Scott Card attributes the idea of “America” to Ben Franklin. The idea of America was the notion that all of the 13 colonies were part of something larger. The idea of America was there in the real world as well, in 1787. In the first half of The Federalist Papers #2, John Jay called on this idea of America.

The heart of John Jay’s appeal to the idea of America is in these five passages:

It is well worthy of consideration therefore, whether it would conduce more to the interest of the people of America that they should, to all general purposes, be one nation, under one federal government, or that they should divide themselves into separate confederacies …

… independent America was not composed of detached and distant territories, but that one connected, fertile, widespreading country was the portion of our western sons of liberty.

Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country to one united people--a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs, and who, by their joint counsels, arms, and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war, have nobly established general liberty and independence.

… an inheritance so proper and convenient for a band of brethren, united to each other by the strongest ties, should never be split into a number of unsocial, jealous, and alien sovereignties.

To all general purposes we have uniformly been one people each individual citizen everywhere enjoying the same national rights, privileges, and protection. As a nation we have made peace and war; as a nation we have vanquished our common enemies; as a nation we have formed alliances, and made treaties, and entered into various compacts and conventions with foreign states.

John Jay acknowledges that he is appealing to a widespread sentiment rather than trying to create a new sentiment: “Similar sentiments have hitherto prevailed among all orders and denominations of men among us.” Famously, at the time of the Civil War, Robert E. Lee, among others, felt a greater loyalty to their State than to “America.” But loyalty to “America” was already something of a tug to the heart of many then and back in 1787.

Just as many Americans in the 18th and 19th centuries felt both a tug of loyalty to their state and to America as a whole, many of us in 2019 feel a tug of loyalty both to our nation and to cross-national values such as human rights and truth, or to a cross-national religion. Some feel loyalty toward both their nation and to supranational ideas like the idea of “Europe” embodied in the European Union. Important world events are now being driven by the balance of power in loyalties within individual hearts between national, subnational, supranational, religious and general human loyalties. What lies behind the relative strength of each of these loyalties in individual hearts deserves much more study and much more pondering than it has received. I said an early version of this in my June 29, 2016 column, “Nationalists vs. Cosmopolitans: Social Scientists Need to Learn from Their Brexit Blunder.” Events since then have only reinforced the importance of understanding the tug of various loyalties in individual hearts.

John Jay did not put the idea of America into the hearts of his readers, but he evokes it well. Here is the complete text of the first half of The Federalist Papers #2, showing the context for the passages I quote above:

Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence

Author: John Jay

To the People of the State of New York:

When the people of America reflect that they are now called upon to decide a question, which, in its consequences, must prove one of the most important that ever engaged their attention, the propriety of their taking a very comprehensive, as well as a very serious, view of it, will be evident.

Nothing is more certain than the indispensable necessity of government, and it is equally undeniable, that whenever and however it is instituted, the people must cede to it some of their natural rights in order to vest it with requisite powers. It is well worthy of consideration therefore, whether it would conduce more to the interest of the people of America that they should, to all general purposes, be one nation, under one federal government, or that they should divide themselves into separate confederacies, and give to the head of each the same kind of powers which they are advised to place in one national government.

It has until lately been a received and uncontradicted opinion that the prosperity of the people of America depended on their continuing firmly united, and the wishes, prayers, and efforts of our best and wisest citizens have been constantly directed to that object. But politicians now appear, who insist that this opinion is erroneous, and that instead of looking for safety and happiness in union, we ought to seek it in a division of the States into distinct confederacies or sovereignties. However extraordinary this new doctrine may appear, it nevertheless has its advocates; and certain characters who were much opposed to it formerly, are at present of the number. Whatever may be the arguments or inducements which have wrought this change in the sentiments and declarations of these gentlemen, it certainly would not be wise in the people at large to adopt these new political tenets without being fully convinced that they are founded in truth and sound policy.

It has often given me pleasure to observe that independent America was not composed of detached and distant territories, but that one connected, fertile, widespreading country was the portion of our western sons of liberty. Providence has in a particular manner blessed it with a variety of soils and productions, and watered it with innumerable streams, for the delight and accommodation of its inhabitants. A succession of navigable waters forms a kind of chain round its borders, as if to bind it together; while the most noble rivers in the world, running at convenient distances, present them with highways for the easy communication of friendly aids, and the mutual transportation and exchange of their various commodities.

With equal pleasure I have as often taken notice that Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country to one united people--a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs, and who, by their joint counsels, arms, and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war, have nobly established general liberty and independence.

This country and this people seem to have been made for each other, and it appears as if it was the design of Providence, that an inheritance so proper and convenient for a band of brethren, united to each other by the strongest ties, should never be split into a number of unsocial, jealous, and alien sovereignties.

Similar sentiments have hitherto prevailed among all orders and denominations of men among us. To all general purposes we have uniformly been one people each individual citizen everywhere enjoying the same national rights, privileges, and protection. As a nation we have made peace and war; as a nation we have vanquished our common enemies; as a nation we have formed alliances, and made treaties, and entered into various compacts and conventions with foreign states.

Don’t miss:

You can find links to my other political philosophy posts here: