On Having a Thesis

My main strategy for helping the students in my Monetary and Financial Theory class is to have them write a lot. They write 3 blog posts a week on an internal class blog. I have showcased some of the best of these blog posts on this blog, “Confessions of a Supply-Side Liberal.” You can see links to all these student guest posts here. The magic of having students write many, many short pieces is something that can be implemented easily by any instructor anywhere who has the good fortune to have a teaching assistant to make brief comments on them all, as I have.* And there is a bit of magic to the blog post format, which tends to disinhibit students. (I know with some degree of confidence, because there was a point at which I switched from having students do short essays that were printed out in one semester of a Principles of Macro class to doing blog posts the next semester. The blog posts were better.)

In this post, I wanted to give a few other tips for writing blog posts in addition to pointing to the magic of writing a lot. The first is that the wind-up in the introduction shouldn’t be too long. Indeed, the most common request from my editors at Quartz when I send them a first draft of a column is that I should shorten the introduction. I often need the lengthy introduction as I write in order to get into the topic, but once the rest of the piece is written, the introduction can be slashed to something much shorter.

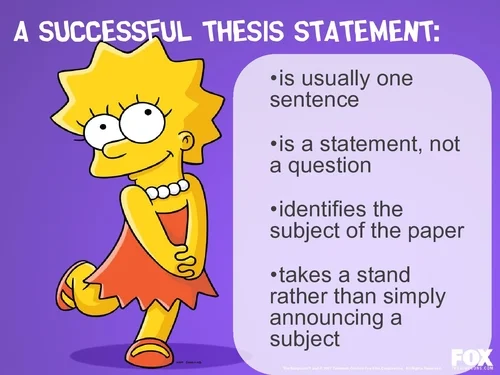

The second tip is that it is important to have a thesis: something that you want to say and are willing to try to back up. If you want some examples of thesis statements, about half the time the titles my editors choose for my Quartz columns are their take on what a thesis statement would be. (You can see a list of titles of my Quartz columns here.) Lisa Simpson above gives some excellent guidance on what a thesis statement should be like; I am afraid the other half of my titles don’t obey these rules for thesis statements.

How can you come up with a thesis statement, and arguments to back it up? There may be other harder ways to come up with a thesis statement, but the easiest way is to think of something you want to say that you actually believe. For most people this is definitely the way to go if you are allowed to choose from a broad range of topics.

To come up with the thesis statement itself, read the newspaper, read other people’s blogs, read books, talk to people, and constantly keep a look-out for any reaction you have that makes you want to say something to the world or at least to some other people. Figure out how to say the gist quickly, so that it can fit in one sentence. It might have to be only an approximation to what you really want to say to fit into one sentence, but that is OK. If that kind of brevity is hard for you, get a Twitter account and practice saying things in 140 characters or less on Twitter. (You can see my tweets here. I think they provide many examples of thesis statements, though not always the supporting arguments!)

The thesis statement does not always have to actually appear in your post or essay, but it needs to exist and you need to know what it is. And I recommend that beginning writers actually put the thesis statement into the post or essay.

In addition to the question “What am I trying to say here?” the question “What am I trying to accomplish in this piece?” is also helpful in identifying a thesis statement. But once you answer “What am I trying to accomplish in this piece?” you need to go back to the question “What am I trying to say here?” in order to come up with the thesis statement itself.

Trying to support your thesis statement can seem daunting. But anything that would make someone a little more likely to agree with your thesis statement counts as supporting it. Even “preaching to the choir”—that is, making someone who already agreed with you more energized to spread the word or to do something about it—counts.

To come up with arguments to back up your thesis statement, ask yourself why you believe it. (Remember, I am only telling you the easy way to come up with thesis statements and back them up. Learning how to argue for something you don’t believe is an advanced writing skill for folks like lawyers.) If you ask yourself why you believe it and can’t come up with anything, maybe you should choose another topic. If you can answer that question, write down the answer, and you are on your way.

There are different levels of arguments you can have for a thesis statement. The upper level is when you have arguments that might convince someone else even if they start out a bit skeptical. In other words, if you can take on the burden of proof and meet that with your arguments, that is impressive.

The lower level of supporting a thesis statement is to explain why you believe it and to lay out what someone else would have to do to convince you otherwise. That is, if you can defend your thesis statement against an attack when the attacker has the burden of proof, that definitely counts for something.

The point is to have a clear thesis statement, and support it as well as you can. Admitting where you might be wrong and where there are weaknesses in your line of argument can be nice, too, although it doesn’t work as the substance of the whole post! If you actually think you might be wrong, that itself can make a good thesis statement: “I used to think X, but now I realize that I just might be wrong, because ….”

That leads into my last tip. An essay is more memorable if there is a bit of conflict or drama in it. For example, “So and so says X, but they are wrong”; or “The conventional wisdom is X, but …”; or “Here is an issue that is extremely important that needs to be addressed; here is what needs to be done”; or “Here is something that will change the world in a big way.” To get that drama you need to have an opposition between two things: for example, two different ways of looking at things; how things are and how they should be; the way things are now and the way things used to be; how things are now and how they will be in the future.

Everything that I am suggesting gets a lot easier with practice. If you keep writing many, many short pieces and keep these tips in mind, you will find your writing getting better and better. Have confidence and just keep going. Being a good writer will give you a huge advantage in your career. And there is a decent chance that, say, around the 25th short piece you write, writing will start to become fun for you.

* To keep the grading burden down, we have a simple check, check+, check- grading system in which there is a strong default toward students getting a check; of the 1/8 of all posts that are revised and sent on to me, I only give a check+ to posts that are at a level worthy of being guest posts on my blog, and we only give check-’s to blog posts that exhibit either obvious low effort or a disregard of instructions.

In addition to making the grading effort reasonable for a teaching assistant (in a 40 student class) despite the large number of blog post writing assignments, giving most posts a check helps to avoid premature perfectionism, which is one of the biggest dangers in learning to write. The blog post format also helps to reduce the danger of premature perfectionism, since the traditions for the blogosphere allow for a certain rate of typos, grammatical errors and awkward phrasing. This makes gaining fluency in writing blog posts in English quite doable even for students for whom English is a second language.

It is easy to continue to polish blog posts after their initial posting. But even if initial posting is delayed until after polishing, it is possible to keep the polishing from creating writers block if the polishing is separated from writing the first draft of a post.

It is hard enough getting ideas down in any form. Don’t burden your writing by requiring too much polish on a first draft. With experience, your first drafts will start looking more polished, but if you want to be a fluent writer, difficult polishing must always be delayed until after getting the first draft down.

Update: Since I wrote this, I have instituted in my class a requirement that students put an explicit thesis statement at the top of their posts. (I do not require that the thesis statement be made part of body of the post itself, in accordance with what I said above: “The thesis statement does not always have to actually appear in your post or essay, but it needs to exist and you need to know what it is.”) I think this is helping a lot in making the posts more focused.